The astonishing tale of William Alexander Morgan has been a PBS documentary (American Comandante), the source of two books (The Yankee Comandante: The Untold Story of Courage, Passion and One American’s Fight to Liberate Cuba and The Americano: Fighting with Castro for Cuba’s Freedom), and a lengthy story in the New Yorker.

Now it’s scheduled to hit the big screen starring Adam Driver (of Stars Wars sequel trilogy fame) as the American all-round loser, mobster hoodlum, bar bouncer, and circus fire-eater and clown who ran guns to Cuba, then joined a guerrilla army unit fighting thuggish and corrupt dictator Fulgencio Batista, rose to the level of Comandante, and became a genuine Cuban hero before being executed for treason against the bullet-pocked walls of La Cabaña fortress.

It’s a riveting tale that Hollywood couldn’t have come up with if it tried!

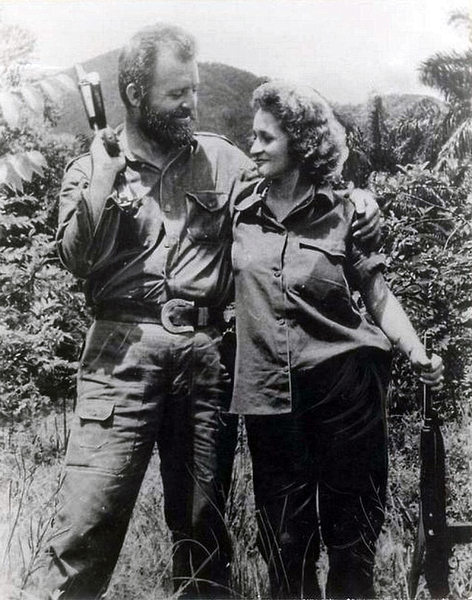

Throw in a true-love romance between Morgan and female revolutionary Olga Rodríguez Farinas, whom he marries while fighting in the mountains (just like Che Guevara with Aleida March, and Raúl Castro with fellow guerrilla Vilma Espín; see Aleida March’s Remembering Che: My Life with Che Guevara)…

Spice it up with Morgan, post-revolution, as double-agent in Miami for Castro getting a fast-one over on J. Edgar Hoover and the FBI while foiling a coup attempt against Castro by a cabal of his former mobster bosses and Rafael Trujillo, evil dictator-president of the Dominican Republic…

Then have Morgan turn on Fidel Castro in disillusion to save Cuba from communism.

William Alexander Morgan being applauded by Fidel Castro, in Havana, 1959, after foiling a coup attempt by Rafael Trujillo

Arrested for supplying arms to the counter-revolutionaries, he’s executed. His widow, Olga, is arrested as an accomplice and serves eleven awful years in prison until she escapes Cuba in 1981 during the “Mariel boatlift.”

All that’s missing are the evil villains. But wait… inevitably, they’re there, too, (in the Americans’ telling) in the personas of Fidel Castro and Che.

Phew! No wonder George Clooney optioned the movie rights a decade ago when Grann’s profile appeared.

Learning recently that director Jeff Nichols was scheduled to shoot the feature film this year, I decided to bone up a bit more about a character whose name I’d previously come across only briefly (having missed David Grann’s May, 2012, New Yorker profile). So I bought The Yankee Comandante, by Michael Sallah and Mitch Weisse (Lyons Press, 2015).

Morgan’s larger-than-life story is so riveting it would be hard not to be enraptured by The Yankee Comandante. The book is well-told, as you’d expect from two Pulitzer Prize-winning authors. But the fact that Mitch Weiss also co-authored Hunting Che should have tipped me off to the problem I have with The Yankee Comandante.

Hunting Che, while excellent and gripping in its story-telling, I found to be a political hack job in which Che is portrayed solely in the pejorative jargon of right-wing acolytes. And although in The Yankee Comandante, Che’s treatment is not quite that of a “bloodthirsty monster” (the favorite term of Cuban-American mythology), it’s not too far short. Meanwhile, Sallah and Weisse’s presentation of Fidel (amounting to surprisingly little treatment) is wholly that of the scheming Machiavellian dictator-to-be.

As investigative journalists, one would have expected Sallah and Weisse to have researched far more widely, and to have profiled far, far more deeply the nuanced contextual milieu of the times and the politics, personalities, and events they portray. The reader simply isn’t given such context!

Worse, the authors also play loose with the facts. (All too often it appears purposeful, as when Sallah and Weiss write that “Castro barked over the radio that the country needed a new provisional president. Then he proceeded to name fifty-nine-year-old provincial judge Manuel Urrutia Lleó… He had iced out the Directorio.” In fact, on July 12, 1958, six months before Batista fled Cuba, all eight competing revolutionary groups, including the Directorio and Fidel’s 26th July Movement, had signed off on Urrutia being named provisional president after Batista’s overthrow. That said, there is no doubt that Fidel, after getting himself named prime minister, craftily forced Urrutia’s resignation to consolidate a power grab.)

Sallah and Weiss are guilty of either very sloppy journalism, or a malodorous political intent. To whit: a review of their “Notes on Sources” reveals a near total dependence on sources that are hardly neutral. Almost all are former members of the Second National Front of the Escambray who would go on to be angry anti-Castro dissidents based in Miami. So the tone of their portrayal of Castro and Che, and Menoyo & Co., is pre-ordained.

Other than that, it’s a great read.

Here, it’s important to note that as a pudgy twenty-nine-year-old. Morgan had not joined Fidel’s 26 July Rebel Movement. Succumbing to his quest for adventure when he signed on to smuggle guns from Miami in December, 1957, it happened by chance to be for a rival group: the relatively small “Second Front” guerrillas of the Directorio, led by Eloy Gutiérrez Menoyo, based in the Sierra Escambray mountains in west central Cuba (Fidel’s Rebel Army was in the remote Sierra Maestra, in the far east of the country). Morgan proved himself so worthy a guerrilla that he essentially became Menoyo’s right-hand man.

Menoyo opposed the profound social transformations in Cuba’s life that were integral to Fidel’s revolutionary goals of not simply toppling Batista, but rectifying Cuba’s appalling social and economic inequities. After Batista was toppled, Menoyo therefore refused to let his guerrilla band be absorbed into Fidel’s Rebel Army. As Fidel reneged on his promise of democratic elections and veered towards communism and, in the face of increasing U.S. hostility, the Soviets, Menoyo reconstituted his unit in the Escambray as a counter-revolutionary, anti-Castro group supported and re-armed by Morgan… and the CIA, which was preparing the imminent Bay of Pigs invasion by Cuban-American exiles.

Morgan had been court-martialed in 1948 and dishonorably discharged from the U.S. Army for going AWOL and then escaping from the brig (for which he served three years in jail). He had also abandoned his wife and two kids before signing up for his Cuban adventure in 1957. But fighting in the Escambray mountains (where he led rebel troops to victory in several key battles, and was promoted to the rank of commander), he became captivated by the Cubans’ willingness to risk their lives to topple Batista. Morgan came to believe in their desire for a “free” Cuba. Perhaps, as much as for anything, because it gave him a chance to redeem himself, to finally become part of something worthwhile. He had reinvented himself, transforming from a failure to a hero and celebrity who believed and shared in a cause.

Fidel Castro and comandantes Che Guevara, Camilo Cienfuegos, António Núñez Jiménez, William Morgan and Eloy Menoyo

He was several times profiled in the New York Times, which in 1958 published his letter “Why I Am Here.” Explaining his participation in Castro’s revolution, he wrote: “I am here because I believe that the most important thing for free men to do is to protect the freedom of others. I am here so that my son, when he is grown, will not have to fight or die in a land not his own, because one man or group of men try to take his liberty from him. I am here because I believe that free men should take up arms and stand together and fight and destroy the groups and forces that want to take the rights of people away.”

The burly, blond, blue-eyed Ohioan was also a product of 1950s American paranoia with communism. It’s natural that he would have responded the way he did to Fidel’s increasingly leftist leanings, and especially since Morgan had joined Menoyo’s Second National Front, not Fidel’s Rebel Army. Had it been the latter, who knows if the outcome would have been different. Most probably not. To Menoyo and Morgan, Fidel, Che, and Raúl were betraying the cause and democratic ideals for which they’d all fought.

“He wanted freedom for my country. He gave his life for my country,” says Morgan’s widow, Olga Morgan Goodwin. “He died for my people.”

While Morgan was executed on March 11, 1961, at the age of 32, Menoyo fled to the USA, where he formed the Alpha 66 paramilitary terrorist group and, in December, 1964, was captured while leading an armed incursion into Cuba. He served 22 years in prison, was then exiled to Spain and, in 2003, after a brief period in Miami, remarkably returned to Cuba where he lived as a “tolerated dissident” until his death in 2012.

Meanwhile, Morgan was targeted by FBI and CIA investigations and, in September, 1959, had his U.S. birthright revoked (shamefully, in response to efforts by congressmen who supported Rafael Trujillo, who had placed a half-million-dollar bounty on Morgan’s head). The Castro government promptly named Morgan a Cuban “citizen by birth.” In 2007, the State Department granted Olga’s request that his citizenship be reinstated.

However, Cuba has never responded to the many requests that his remains be returned to Ohio. They are to be found in a remote corner of Havana’s Cemeterio Colón, while the role of Morgan in la revolución has been expunged.