When lovelorn, fortyish, sound technician Richard Fleming feels his life spiraling into “nightmarish mediocrity,” he determines the escape lies in walking across Cuba (more or less) end to end.

After procrastinating for a few years and gradually sinking into depression, in 2000 he finally decides “to kill my incipient midlife crisis dead in its tracks.” He puts his thriving career on brief hold, then leaves his girlfriend and downtown Manhattan apartment, flies to Havana, takes a bus to Pinar del Río (in Cuba’s western extreme) and starts walking to Guantánamo, in the east.

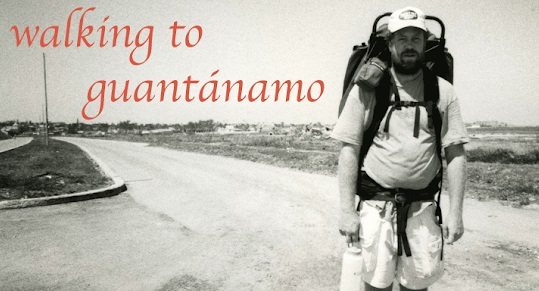

“Other than to make my way to the western city of Pinar del Río, put on my backpack, and walk the thousand or so miles it would take to reach Guantánamo Bay, I really didn’t have much of a plan,” he wrote, taking the simple approach to his journey.

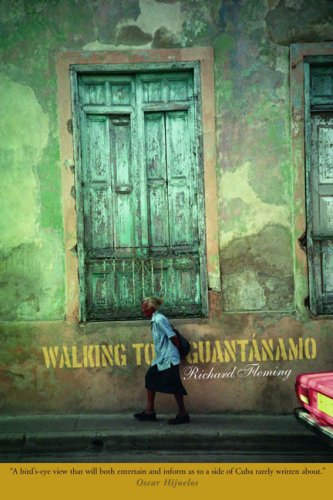

Walking to Guantánamo (Commons Books, 2008, ISBN-10: 0981457916), chronicling his four-month odyssey, is an engaging, entertaining, and edifying debut book by the writer.

Fleming succumbs early to all the sweat and blisters, and his plan to walk across Cuba soon devolves into an errant foray of miscellaneous come-what-may modes of transport that offer some of the few lighter, and occasionally hilarious, moments among his seemingly endless travails and tribulations.

These few moments of comic relief are sorely needed. Overall, the mood is a tad depressing… not least because Fleming himself suffered from beginning to end with what Samuel Johnson (copied by Winston Churchill) coined his “black dog.” Not an ideal state in which to see, feel, and revel in all things positive. Instead, almost all he sees of Cuba’s social circumstance is communist dysfunction, pessimism, and gray cement.

So let’s get the negative stuff out of the way before I point out the good stuff…

In 1996, during my own three-month, 11,000 km motorcycle journey through Cuba end to end, from the Cabo San Antonio lighthouse in the west to that pinning Punta Maisí in the east (see Mi Moto Fidel: Motorcycling Through Castro’s Cuba), I gradually sank into my own depression. To say the least, Cuba increasingly with every mile no longer seemed such a charm. (Thank goodness I soon bounced back to an even fulcrum!) So I can empathize!

Fleming paints a unipolar portrait of overwhelming material deprivation verging on outright poverty. Undeniably, that’s one side of the Cuban coin (and one I’ve profiled in detail in my own eight books on Cuba), and one certainly more noticeable back in 2000 when the country was still struggling to recover from economic desperation following the collapse of the Soviet Union a decade before. But what Fleming omits is the uplifting converse that so endears visitors to Cuba (read on for more).

Worse, Fleming is guilty of being tacaño—a skinflint.

He’s constantly trying to barter fair deals down, despite harping on constantly about how everyone he meets hasn’t got two pesos to rub together and is desperately hustling to make ends meet. In walking (actually a third way through his journey he tires, and thereafter travels by hitchhiking, bus, and eventually by pedaling a hefty Flying Pigeon bike) he seems to believe he’s earned the right to pay the same low peso price as Cubans. (Back in 2000, Cubans earned the equivalent of about $18 a month in a twin-currency, heavily subsidized economy in which, by default, every foreigner was, and remains, a comparative millionaire.)

“Cuban restaurants that do not cater solely to tourists often have two almost identical menus, one in dollars and the other in pesos,” writes Fleming. “The peso menu, with complete meals for less than the equivalent of a dollar, shows prices typically a fifth of those on the dollar menu. Usually a decent command of Spanish and the firm insistence that you are aware of this institutionalized clipping [ITALICS MINE] is enough to embarrass restaurant proprietors into bringing out the peso menu… It rather took away my appetite to see the owner, frustrated and annoyed at his failure to fleece me [ITALICS MINE] of my dollars, go storming off into the kitchen to prepare the order we had finally settled on.”

It’s difficult not to revel in the author’s well-deserved trials and tribulations after such cheapskate bullshit as that!

Nonetheless, in all other regards, Fleming has produced a splendid and surprisingly self-deprecating and wry travelog, told with humility (or at least full of self-doubt) and full of adventure and color.

The author’s own deep interest in birdwatching, and in popular music and Cuba’s complex spiritual life, inform Walking to Guantánamo. His in-depth and learned portrayal of popular culture and daily life is keenly observed and wonderfully expressed, especially his probing into the soul of Cuba through its music and Santería Afro-Cuban religion. These extensive profiles are lively, full of energy, sharply focused (with regards to music) by his own professional experience and expertise as the perfect lens, and supported by succinct yet encyclopedic historical and social context.

Curiously, however, he offers no questioning analysis of the numerous Santería (and outside Guantánamo, with its Haitian heritage, Vodú) practices in which he participates. Although his evocative descriptions are superb, he doesn’t write of the participants believing themselves possessed by spirits, for example, but presents it as unquestioned fact. That perhaps a majority of Cubans believe such superstitious nonsense is no reason to represent it as truth. I found it irritatingly condescending.

Otherwise, his quixotic journey by foot and behemoth bicycle (and, along the way, everything else from open-backed trucks to donkey carts) takes on a vista unblinkered by either misplaced romanticism or ideological attachment.

His political commentary is noticeably sparing. Fidel, for example, barely gets a mention. There is no portrayal of Cuba pre-Revolution, with its rural and urban misery as a counterpoint to the modern and wealthy (and overwhelmingly white) Havana of popular vision. Nor any reflection on the “golden years” of the Soviet period, which so many elderly Cubans wistfully look back on with fondness. And an analysis of the impact of the U.S. embargo in the woes he profiles in Cubans’ lives is entirely missing, other than this single sentence: “The absurd American embargo, a policy that benefits no one save a few Havana propagandists, lingers on.”

No doubt true, but here Fleming oddly offers no mention of the Cuban-American community and its propagandists who work to keep the embargo in place. And once he arrives in Guantánamo, his profile of U.S.-Cuban relations is perfunctory; noticeably so given the huge import that the naval base has played in the two countries taut relations for more than a century. Here, the book would have benefitted immensely from the historical profiles, in particular, of prostitution (which sustained the local economy in pre-revolutionary times) offered by Tom Miller in his Trading With the Enemy: A Yankee Travels Through Castro’s Cuba. (Also see my recent book review of Ada Ferrer’s superb, recently released Cuba–An American History.)

So, too, his portrait of the Revolution’s failed promises and aspirations isn’t balanced by its laudable achievements and, indeed, beauty—the fabulous value system, the magnificent sense of community, the universal literacy and health care, the laughing children that reminded James Michener, on his own six-day visit in 1988, of “a meadow of flowers. Well nourished, well shod and clothed, they were the permanent face of the land.” (See Michener’s Six Days in Havana.)

Fleming saves much of his political analysis for his very excellent epilogue, where he admits: “Stumbling through the country by any means necessary, lonely and gloomy and with my aspirations diminishing almost daily, I was plagued with the thought that my dark mood was clouding my view of Cuban society. And doubtless it did.”